Voice of America News (VOA) reported on Tuesday that while the international community is nervously monitoring the brutal war between factions of the Sudanese junta and scrambling to deal with the ensuing humanitarian disaster, Communist China is moving full speed ahead with plans to “advance its own interests” in Sudan’s oil and mineral resources.

Fighting broke out on April 15 between Sudanese army commander Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and his former junta partner, Mohamed Hamdan Daglo, leader of the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF). The two appear to be evenly matched in the power struggle, leading to a grinding war of attrition in which fighting scarcely slows down for so-called “cease-fires.” Burhan and Daglo have said the conflict will continue until one of them is dead.

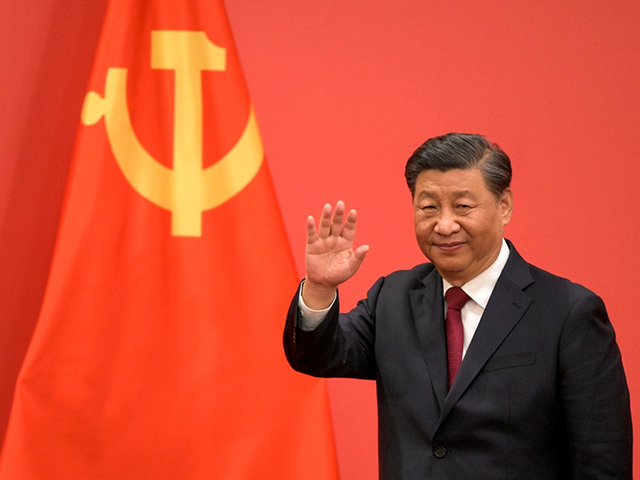

China Seeks Stronger Ties With Sudan Amid Regional, International Tug-of-War: https://t.co/ZP0Y9u5TYI #Sudan #China #ChinaInAfrica pic.twitter.com/Mi0KFysQCh

— allAfrica.com (@allafrica) May 31, 2023

The United Nations International Organization for Migration (IOM) said last week that over 1.3 million people have been displaced by the fighting in Sudan, with hundreds of thousands fleeing across the border into Egypt, South Sudan, Chad, Ethiopia, the Central African Republic, and Libya. Sudan’s hospitals and clinics are overwhelmed with casualties, and many facilities have been deliberately attacked or captured by the warring factions.

VOA noted that China is maintaining a “neutral stance” in the conflict while protecting its considerable investments:

China played a key role in developing Sudan’s oil fields before the country split into north and south in 2010, investing close to $3 billion, according to some sources. Chinese workers built much of the project’s infrastructure before it was handed over to the newly independent South Sudan. A pipeline to transport the oil continues to flow through the north of Sudan, where it is ultimately shipped from Port Sudan.

In 1959, Khartoum became one of the first Arab states to recognize the People’s Republic of China. Medical aid and construction projects like the People’s Hall in Khartoum were signature pieces of early cooperation between both countries.

China also has major interests in Sudanese mining and agriculture, including gold mines, and it covets Sudanese territory as a key element of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), because China needs Red Sea ports. Even as the ruling junta makes war against itself, China also sees Sudan as an important piece of the African political puzzle.

“Sudan is a big part of China’s overall strategy in the region to bring east and North Africa more on its side. It has a lot to do with business, investments, infrastructure and even education, including teaching Mandarin to Sudanese,” Middle East analyst Paul Sullivan of the Atlantic Council told VOA.

“Sudan is a significant player in the Nile Basin but is weak and uncertain now, but has great potential with the right leadership. Instability and uncertainty open Sudan up to exploitation by other countries, terrorists, and organized crime,” Sullivan said.

Several analysts told VOA that Sudan is an important test of the recruiting strategy for China’s rising axis of tyranny. China saw an opportunity to make deals with the noxious dictator Omar al-Bashir in the late 90s while the U.S. was imposing sanctions against his regime. Today, China cuts deals with and makes loans to despotisms and turbulent nations without asking “questions about human rights and democratization like the U.S. does,” as Egyptian sociologist Said Sadek put it.

The Diplomat wondered in early May if China might not flex its diplomatic muscles (and use its economic leverage) to work out a peace deal in Sudan. Such an accomplishment could be added to the rapprochement China recently brokered between Saudi Arabia and Iran to burnish Beijing’s credentials as the most important diplomatic force in the post-American world.

The problem with that strategy, according to the Diplomat, is that China lost a great deal of influence in Sudan after Bashir was deposed in 2019 and China’s hefty investments in energy and minerals are “deeply intertwined with the politics and economics of the Sudanese conflict,” not least because both Burhan and Dagolo hold major stakes in Sudan’s leading oil and mining companies. Both faction leaders would probably respond poorly to China using economic leverage against them.

That would leave Beijing an opening to work in the “gray areas unaddressed by neoliberal peace offers,” essentially by convincing Burhan and Dagolo that neither their interests nor China’s would be served by burning Sudan to the ground:

This would look like Beijing leveraging its historical links with Sudan by convincing the two warring sides to resolve their differences through a multi-partisan-adjudicated mediation framework; requesting humanitarian ceasefires and safe passage for refugees and internally displaced persons; and introducing an international coalition of peacekeepers that would, at least in the short term, curb the spread of the civil strife across the country.

A further reason rests in the unique level of operational capacity that Beijing possesses in the country. China, for instance, successfully evacuated thousands of its citizens and those of other countries in the initial phases of the war when the rest of the world failed to do so. This was possible owing to China’s diplomatic advantage in actively engaging warring elements in securing concessions for Chinese citizens and associates.

In theory, Beijing can equally employ this leverage to push for an end to hostilities in Sudan, especially given the distrust that persists among the two generals against the collective West on one hand, and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) group on the other.

Interestingly, Beijing appears to have done none of these things in the month since The Diplomat suggested them. The Chinese could be reluctant to back the wrong horse in the race for power in Khartoum and see the winner turn against their interests, they might fear pushing the wrong buttons with Burhan or Dagolo could lead to a regional conflagration that damages many other valuable Chinese interests, or they might simply have concluded there is no way to get the factions in Sudan to stop fighting until one of them wins.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.